How to survive to unaffordable cities: cooperative housing

Living in cities such as Barcelona is a nightmare: crazy prices, ugly and unsustainable flats, schizoid and greedy landlords, expensive groceries. It's time to build the alternative.

As I write this, a man, Zohran Mamdani, is running in the Democratic primaries for New York City mayor on a platform to make the city affordable for working-class people. His plan? City-owned grocery stores, free and fast buses, and a rent freeze for the two million residents in rent-stabilized apartments.

How will he pay for it? By taxing millionaires.

Tax them—they’re not leaving New York. Look:

But let’s take a step back and why are we talking about house crisis in Europe and more or less in all the big cities of the “western bloc”?

WTF happened to Barcelona?

Barcelona is one of the most beautiful cities in the world—no one can seriously argue otherwise. It’s a wealthy city with an international airport, a cruise port, industry, fintech, biotech, universities, expats, foreign investment funds, and tourism.

If a city has strong pull factors—a vibrant cultural scene, a solid industrial base that provides decent wages to workers, students, and migrants—then what’s the issue? These people are part of the city. They live in it, grow with it, and help it thrive.

Here’s where the real problem starts: the 2008 financial crisis. Spain—along with Greece, Italy, and Portugal (mockingly grouped as the “PIGS”)—was hit hard. People couldn’t pay mortgages or rents. Evictions surged. In the middle of this chaos, foreign investment funds like Blackstone swooped in and bought up thousands of apartments in Barcelona, Madrid, and other cities.

At the same time, tourism exploded. Airbnb and other short-term rental platforms took over, making it even harder for workers, students, and young people to find long-term housing. Airbnb is a big part of the problem. Justifying short-term rentals as a way for middle-class families to make ends meet is, frankly, disgusting—especially when politicians like Elly Schlein, head of Italy’s Democratic Party, parrot that line on national TV just to appease her party’s liberal-conservative wing. Even more disappointing when it happens on the same show that features Ada Colau, the former mayor of Barcelona with Barcelona en Comù, who says the exact opposite.

Look:

So, we’ve got the aftermath of the financial crisis, out-of-control tourism, and now—expats.

But who are expats, really?

“The term expatriate is commonly used to refer to skilled workers or professionals who take positions outside their home country, often temporarily.” (IOM Glossary on Migration, 2019)

In many cases, they’re digital nomads and high-skilled remote workers who are wreaking havoc on housing markets across major cities. They show up, stay for 6 to 9 months, and move on. They’re not citizens. They don’t build community. The city—whether it’s Barcelona, Lisbon, or Bangkok—is just another stopover. It's not their home.

Expats often earn far more than local workers. That means they outbid Catalan families for housing, driving up rents and pushing locals out. They take over flats that used to be homes, now turned into co-working spaces or boutique rentals. What enables all this? Bad policy. Urban renewal projects that gentrify working-class neighborhoods, and a lack of serious investment in public housing.

The result is an unsustainable situation.

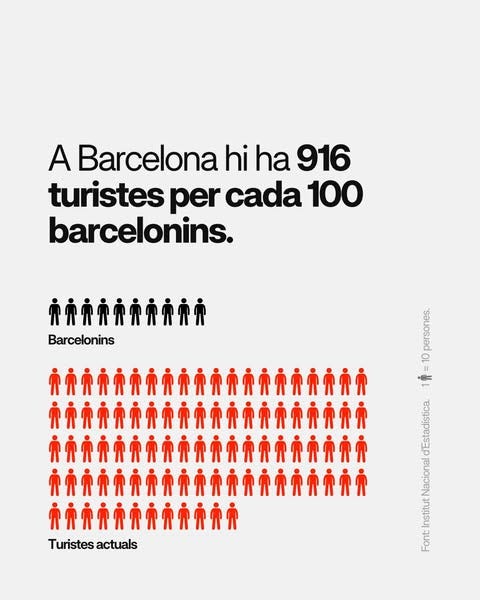

Just recently, Barcelona En Comú launched a campaign against expanding the city’s airport—a plan that would double the number of tourists from 15 million to 30 million per year. Barcelona already sees more tourists than Brazil or Australia. Right now, there are 916 tourists for every 100 residents.

Now imagine this new wave of tourist invasion hitting a country where rents have risen 80% over the past decade, far outpacing wages. A recent Bank of Spain report found that nearly half of Spain’s renters spend 40% of their income on rent and utilities, compared to an EU average of 27%.

While the national and Catalan governments drag their feet, citizens in Barcelona and other cities have started pushing back—protesting the touristification of their neighborhoods, even using water guns to symbolically “shoot” at tourists. Honestly? Fair enough.

Casa Orsola is just one example of resistance. It’s a case of people standing up to gentrification, overtourism, and the wave of incoming expats—all fueled by a practice known as “silent evictions.” Here's how it works: landlords or investment funds—like Lioness Inversiones in this case—keep raising the rent until tenants are forced out, so the units can be flipped into short-term rentals.

Another form of resistance is building alternatives—rethinking housing beyond just public or private ownership, and focusing on the commons.

Housing Cooperative: La Borda

La Borda is a powerful example of what it means to focus on the commons—and of what good housing policy can look like.

As the cooperative describes it, their mission is to “guarantee access to decent, social, affordable, and environmentally sustainable housing, with the aim of fostering new forms of coexistence and building community through interaction between neighbors.” On top of that, La Borda is grounded in “the values of feminist economics and the social and solidarity economy.”

The core principles of a project like this include:

Grant of use: “the property will always be collective, while use is personal. Residents have the status of cooperative partners and can live there for life. The General Assembly is the main sovereign institution where the decisions are made. This model eliminates property speculation and profiteering on a fundamental right like housing. Members can not sell or rent the flat. It is an alternative model of housing access to the traditional ownership and rent, with a strong commitment with the use value above exchange value.”

Leasehold: “This right (limited right to use rather than traditional private ownership—residents don’t own the flats outright, but hold usage rights for a long-term period.) lasts for 75 years and involves paying an annual fee.

Rating the land as HPO (State-Subsidized House) involves that potential members cannot exceed a maximum income to benefit from the right of use of a flat in the cooperative. It also establishes a maximum fee to be charged for the housing use, in order to allow humble people to have access to them, one of the main purposes of the cooperative.”

Funding: “The project will be funded by the social economy, ethical banks and voluntary contributions made by groups and individuals. […] The cooperative’s solvency is based on the monthly fees associated to the use of the apartments. As a non-profit cooperative committed to social impact, we have to use the total amount of surplus to promote the access to decent, efficient and affordable housing, through the housing cooperative model of grant of use.”

Life in common: At La Borda you find shared common spaces and services, including communal kitchens and laundry rooms and a deep emphasis on community solidarity where residents support each other financially if someone struggles to pay rent, and come together to share meals and celebrate life events.

Architecture: Everything was developed through participatory design, meaning future residents worked closely with architects to shape the project. This led to a strong focus on both sustainability—with renewable energy, efficient systems, waste reduction, and bioclimatic architecture—and collective living, with modular apartments that can adapt to different needs (families, couples, seniors, young people, etc.).

In short, La Borda shows how cities can fight back—against overtourism, financial speculation, deindustrialization, and gentrification. It’s proof that a different urban future is possible.

Now it’s up to us to build that future, wherever we are.