Energy Communities: Converging, Organizing and Spreading

Establishing energy communities is the only way to energy independence and security

Since the first post on this newsletter — and especially if you know me in person (I think 99.9% of the subscribers know me personally) — you probably already understood my opinion about how stupid I find the debate around what you should do or which books you should read to be considered a good leftist: no, I’ve never read Capital by Karl Marx, no, I’ve never read all of Gramsci’s books, and I’ve never finished Che Guevara’s diary. Good.

Now I’ll just take 2 minutes of your time to help you understand—thanks to a speech by Kai Heron that I listened to at the 2024 Summer School of Political Ecology in Ljubljana—the fundamental difference between two political theories on how the left should act in response to the climate crisis. If you’re really, really interested, the full lecture is in the video below.

We have two opposing camps debating the question: “How can the left (and the world) survive the climate crisis?” They are: Degrowth (vamoooos) and Eco-Modernism (buuuuuu).

[Degrowht] claims that the growth-based paradigm — capital’s endless material and energetic throughputs, the use of gross domestic product (GDP) as the measure of a healthy society, and an ideology of progress determined in accordance with capital’s priorities — is a barrier to a post-capitalist future. To disentangle our collective reproduction from capital, radical versions of degrowth have called for reductions in material and energetic throughputs in the imperial core, ecological and climate reparations, technology transfers to support a global green transition, global developmental convergence, and reductions in personal consumption for heavy consumers.

For left eco-modernists — as opposed to reactionary eco-modernists, or capitalists — degrowth is both unnecessary and politically poisonous.It’s unnecessary because technological advances in hydrogen fuel, carbon capture and storage, nuclear energy, and renewable energy systems means that a high-consumption lifestyle for all is possible providing capitalism is abolished and workers take control of the means of production. It’s politically poisonous because, as Cale Brooks writes in Damage Magazine, degrowth is a ’politics of less’ that cannot rally support among workers who are already struggling to make ends meet.

(Kai Heron, https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/news/forget-eco-modernism)

To summarize, eco-modernism argues that we shouldn’t reject capitalism entirely, but rather embrace socialism because the problem isn’t growth itself, but why we grow, how we grow, and the philosophy behind that growth. Degrowth, on the other hand, calls for a full-on revolution in how we conceive of our post–Second World War lifestyle.

The debate is really interesting, but still—we need to act now. And this kind of debate could go on forever, while we simply don’t have that kind of time. So, what can we, the people, do right now without falling into the black hole of individual responsibility as the only path to saving ourselves from extinction—as liberal and capitalist institutions would have us believe? You know, stuff like paper straws... just to be clear.

I honestly think we should move beyond both the private and the public as models for organizing society, and instead adopt the category of “the commons” as a theoretical framework to reorganize society from the grassroots level. It would be especially important to apply this approach in the energy sector as well.

Kai Heron talks about Public-Commons Partnerships as a way to democratize the production and management of resources, challenging the power of capital by expanding the power of workers and, I would add, of communities. We’ll come back to how Public-Commons Partnerships are conceived, but just stay with me for a second: what’s better than a decentralized, grassroots, community-regulated economy to take down two different centralized and hierarchical systems of production and management—like capitalism and socialism?

In the video above, Heron talks about democratizing the agro-food industry, the pharmaceutical sector, housing, and—most importantly for me in this Mildly Annoying Opinions article—energy.

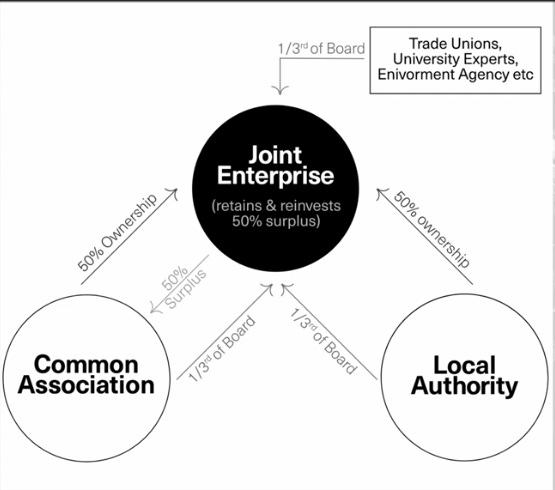

So, let’s talk about the structure of Public-Commons Partnerships (PCPs). Basically, PCPs are co-owned 50/50 by the Commons Association (the community) and the local authority. Seats on the Board are divided as follows: one-third for trade unions, academics, environmental agencies, or similar organizations; one-third for the local authority; and one-third for the Commons Association. Additionally, 50% of the surplus is retained and reinvested into PCP activities, while the other 50% is allocated to the Commons Association.

Why did Heron and his colleagues decide to organize PCPs this way? Because we need to avoid turning them into the usual public-private partnerships. In other words, we need to design PCPs to be “capitalism-proof,” ensuring they can’t be used as tools to de-risk poor private management of public goods.

Example: the state decides to privatize water distribution, and now we have polluted water in our pipes because the water company chose to maximize profits by cutting infrastructure maintenance. Then, the state decides to renationalize the water company to fix the problem caused by private mismanagement. This is exactly why public goods should not be managed by private interests: we usually privatize profits and collectivize damages. That’s the most obvious form of de-risking, and it happens all too often in liberal-capitalist systems.

Derisking is exactly one of the reasons why communities should own their own energy sources. Some of the other reasons are:

Independence from fossil fuels and energy corporations like ENI, Saipem, etc.;

Self-management and emancipation from central political power;

Fighting against energy poverty and discrimination toward the most vulnerable groups;

Community-driven investments, with science-oriented rather than profit-oriented decisions.

Now that we have the theoretical framework for what I believe should be the foundation of a decentralized network of energy communities, let’s start by describing what an energy community is.

The European Commission describes an energy community as a vehicle to enable collective, citizen-driven energy actions that support the clean energy transition. The EU also supports energy communities in the policymaking process by developing these community-driven, fossil-free energy initiatives. However, implementing such communities within the classic liberal-capitalist framework of the European Union will compromise the effectiveness of addressing the reasons I outlined just a few lines ago.

The EU also supports rural energy communities and works to eliminate barriers (such as knowledge gaps, bureaucracy, etc.) that prevent citizens from forming energy communities within the Union.

Nice, but that’s not enough. The proliferation of energy communities run by citizens is still lower than the massive investments from energy corporations in solar farms and other major projects in the renewable energy sector.

The main problem with, for example, solar farms, is that they operate in the same exploitative and colonialist manner as, say, an oil refinery. But "hey, it’s renewable energy. You should be happy you don’t have a coal power plant next to your house." In an era dominated by the climate crisis, large renewable infrastructures built this way won’t help us move away from the philosophy that has already ruined—and continues to ruin—our world.

Another issue is that these massive fossil fuel energy plants are often built in the countryside, taking valuable land away from agriculture. And we still can’t eat discarded solar panels.

Energy communities, especially when organized in urban spaces, provide an important alternative to the oligopoly of fossil fuel companies that supply the energy we need to cook, heat our homes, wash, recharge electric devices, etc. Energy communities in urban areas wouldn’t require new land, as solar panels and small wind turbines could be installed on rooftops, and on a larger scale, over industrial buildings. Another important point is that energy communities don’t have to be built in wealthy areas where companies could make more profit. Grassroots, citizen-run energy communities can be established anywhere there is the will to do so. That’s why, for me, energy communities are emancipatory.

Energy poverty is one of the biggest issues in the world right now. It means that there are people who cannot heat their homes, clean their water, access the internet, or have opportunities for education and work.

Moreover, energy communities organized as Public Commons Partnerships are the best option to merge the decarbonization of the economy with the necessity to save money and the need to avoid sudden shifts in energy policy by governments and market crises.

Good examples can be seen on REScoop, a cooperative network of energy communities across the European Union, but this is not the only possible outcome. I believe that the energy communities I’ve described are also perfect for lifting people out of energy poverty and empowering geographically, politically, and socially marginalized communities in countries outside the EU.

This is what I think: private and state interests will never save us from the climate crisis. We can only save ourselves by organizing an alternative model, and this could be one way to do it.